The Sunflower State is known for its famous lawmen—but its infamous villains are legendary as well

This article was originally featured in the winter 2014 issue of the magazine. Photos are courtesy of the Kansas State Historial Society

Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, Wild Bill Hickok—their names are synonymous with law on the Kansas frontier. Of course, Kansas is known not only for these legendary lawmen, but also for the villains and outlaws whose tales are still told to this day.

In many cases, the fame of these outlaws has overshadowed those who stood on the right side of the law, and their lives have become the subject of legends.

THE DALTON GANG

Although the Dalton brothers—Frank, Grat, Bob, Emmett and Bill—began on the right side of the law, that is not the way most of them ended their lives. Frank died in the line of duty as a deputy marshal, but his brothers eventually became outlaws, with Grat, Bob and Emmett forming the infamous Dalton Gang, often teaming up with outlaws Bill Doolin, Bill Power, Charlie Pierce, George Newcomb and others. The gang soon became known for daring robberies of banks, stagecoaches and trains across Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas and Kansas.

Despite their ability to elude numerous posses, the gang met its fate on October 5, 1892, when Bob, Grat and Emmett, along with Bill Power and Dick Broadwell, attempted to rob two Coffeyville banks at the same time. After they tied their horses in a nearby alley and walked toward the banks, one of them was recognized by Coffeyville citizen Aleck McKenna. As soon as McKenna realized their destination, he raised a cry to alert the townsmen, who rushed in to apprehend the gang. In the ensuing gun battle, all but Emmett were killed. Emmett was seriously wounded but recovered and was sentenced to life in prison. Later pardoned, Emmett married and wrote a book about the exploits of the Dalton gang, which was later made into a movie.

Today visitors to Coffeyville can visit the Dalton Defenders Museum (daltondefendersmuseum.com, 113 E. Eighth St.). They can also visit the grave of Frank Dalton in Elmwood Cemetery while in town; since he was killed in the line of duty as a deputy marshal, his name can be found on the U.S. Marshals Roll Call of Honor.

BONNIE & CLYDE

Although their crimes took place in a number of states, the infamous duo of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow often

frequented the Sunflower State. In fact, they believed Kansas was the best state in the Union for robbing banks because— according to the Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, it had “numerous straight roads, each intersecting every mile or so with another road, creating a network of escape routes virtually impossible to seal off.” Historic interviews suggest that Clyde robbed his first bank in Lawrence, with the help of Ralph Fults and Raymond Hamilton.

Barrow and a couple of gang members tried to hijack a car from a group of people playing croquet in Meade in 1933. That attempt proved unsuccessful, as one of the women present attacked the outlaws with a croquet mallet. Barrow and one of his companions managed to escape, while the third member of the group was captured.

Clyde and his girlfriend Bonnie were much more successful the following year, stealing a new Ford V-8 sedan from the driveway of Jesse and Ruth Warren in Topeka. It was in that car that the duo were killed during an ambush set by law officers in northern Louisiana later that year.

The death car, riddled with bullets, was returned to the Warrens; it has been sold many times and is now on display in Las Vegas. Visitors to Kansas, however, can visit Merchant’s Pub and Plate (746 Massachusetts) in Lawrence: now a restaurant, it was originally a bank believed by many to be the first one robbed by Clyde Barrow.

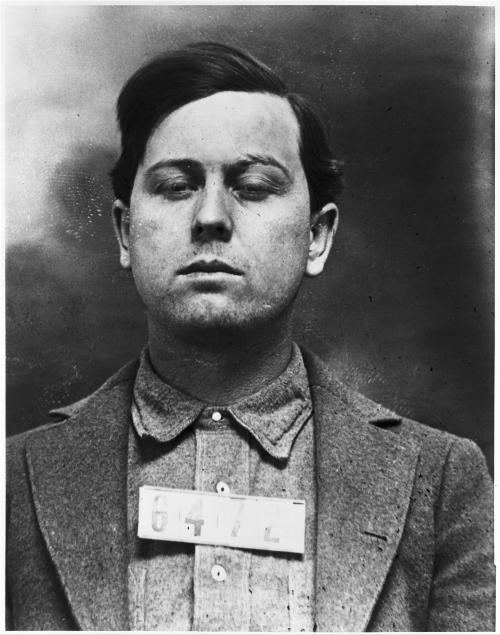

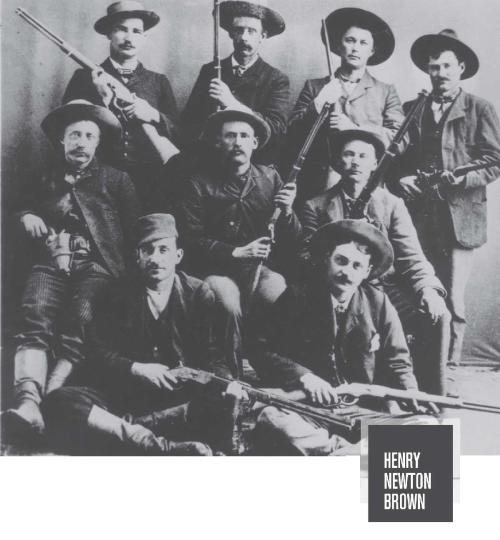

HENRY NEWTON BROWN

The people of Caldwell, then considered the wildest town in Kansas, hired Henry Newton Brown as their assistant marshal in 1882, and were so impressed with his work that they promoted him to marshal five months later.

The town’s grateful citizens presented their marshal with a new, engraved Winchester rifle to celebrate the law and order he brought to their growing community. Area papers wrote of his exploits, proclaiming him one of the fastest guns in the Southwest and remarking on his gentlemanly ways and his freedom from vices. He soon married and purchased a house in town.

But as they lavished praise on him, the people of Caldwell did not know about Brown’s outlaw past. In fact, he had been involved in the Lincoln County War in New Mexico, ridden with Billy the Kid, stolen horses and left New Mexico to avoid murder charges.

Living above his means soon led Brown to return to his outlaw ways; he even enlisted his deputy and two of his outlaw friends into robbing the bank in Medicine Lodge, where he used the rifle that the citizens of Caldwell had given him. Things didn’t go as planned, however, and the four were captured. Brown was killed as an angry mob broke into the jail; the others were hanged from a nearby tree.

The Winchester given to Brown can now be found on display in the Kansas Museum of History in Topeka. His grave can be found in the Caldwell City Cemetery.

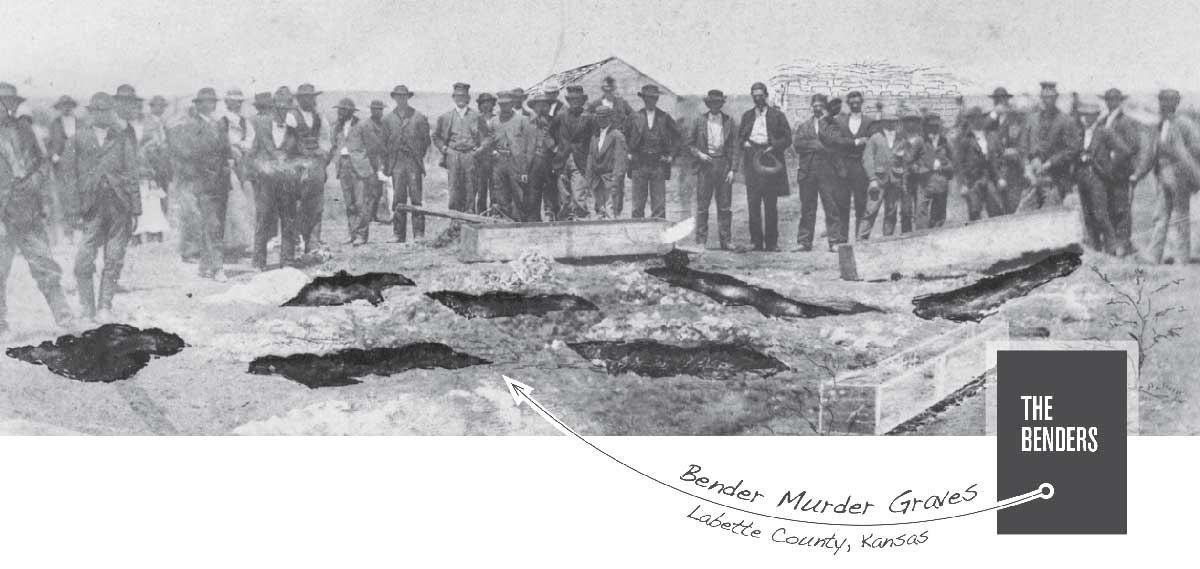

THE BENDERS

When it comes to mass murderers, the Benders of Labette County in southeast Kansas have few rivals. Their story begins in 1871 when the family, consisting of John Sr., his wife, and grown children John Jr. and Kate, built a one-room cabin on the well-traveled road between Independence and Fort Scott. It ends in 1873, when 11 mutilated bodies were found in shallow graves in the orchard behind that cabin, according to the Kansas State Historical Society.

The Benders used a canvas cloth to partition their cabin into two rooms— the one in back for living quarters, the other for a small grocery and inn for travelers. Visitors were encouraged to relax and lean against the canvas after eating a meal at a table in the front portion; when they did so, it is believed that a sledgehammer was used to bash them over the head before they were dragged to a pit below the house, where their throats were cut. The bodies would then be buried in the orchard under the cover of darkness.

The disappearance of an Independence physician along the road prompted a search of the area and led to the discovery in the orchard. By then the Benders had disappeared, never to be seen again. To this day no motive has been found for their crimes; since most of the victims had little money or anything of value with them, it is believed the Benders murdered their victims for the sheer thrill of killing.

Today a historical marker stands in the rest area at the junction of U.S. Route 400 and U.S. Route 169 near the site of the Bender cabin, which is rumored to be haunted. Artifacts such as hammers found in the cabin as well as newspaper clippings and photos of the cabin being moved in 1873 while authorities searched for more bodies can be found in the Cherryvale Museum (215 E. Fourth St. in Cherryvale).

Although these Kansas outlaws are long gone, tales of their lives and infamous deeds will undoubtedly continue to intrigue future generations.