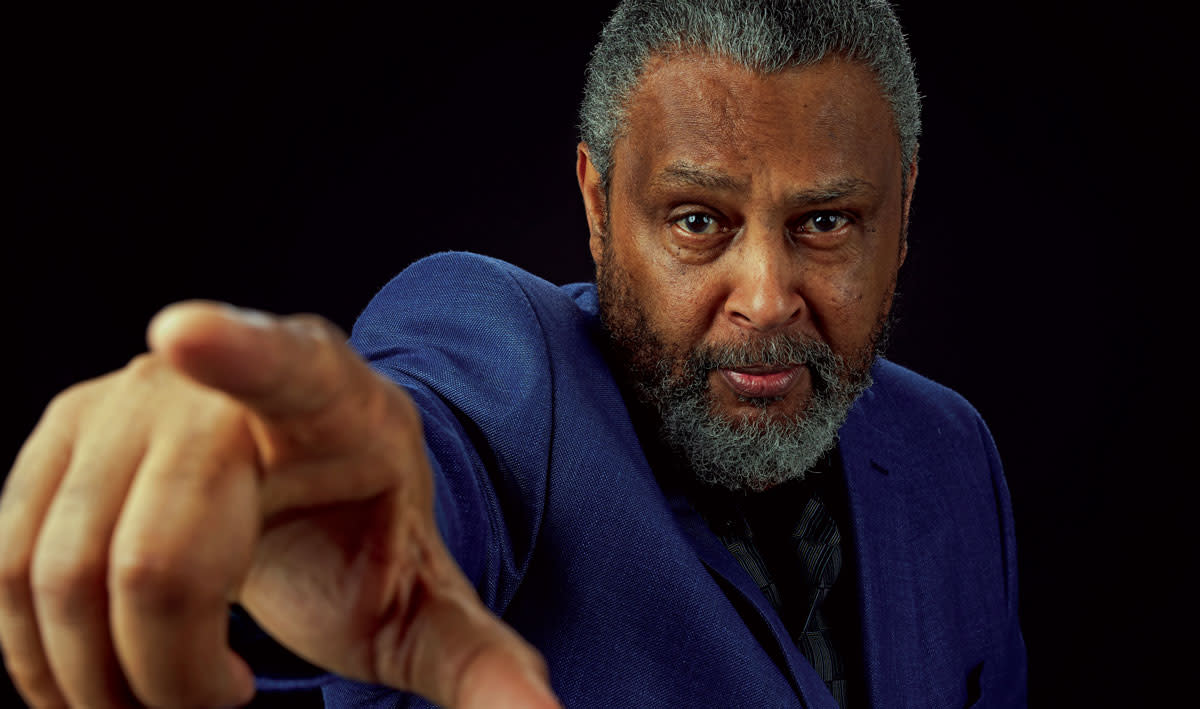

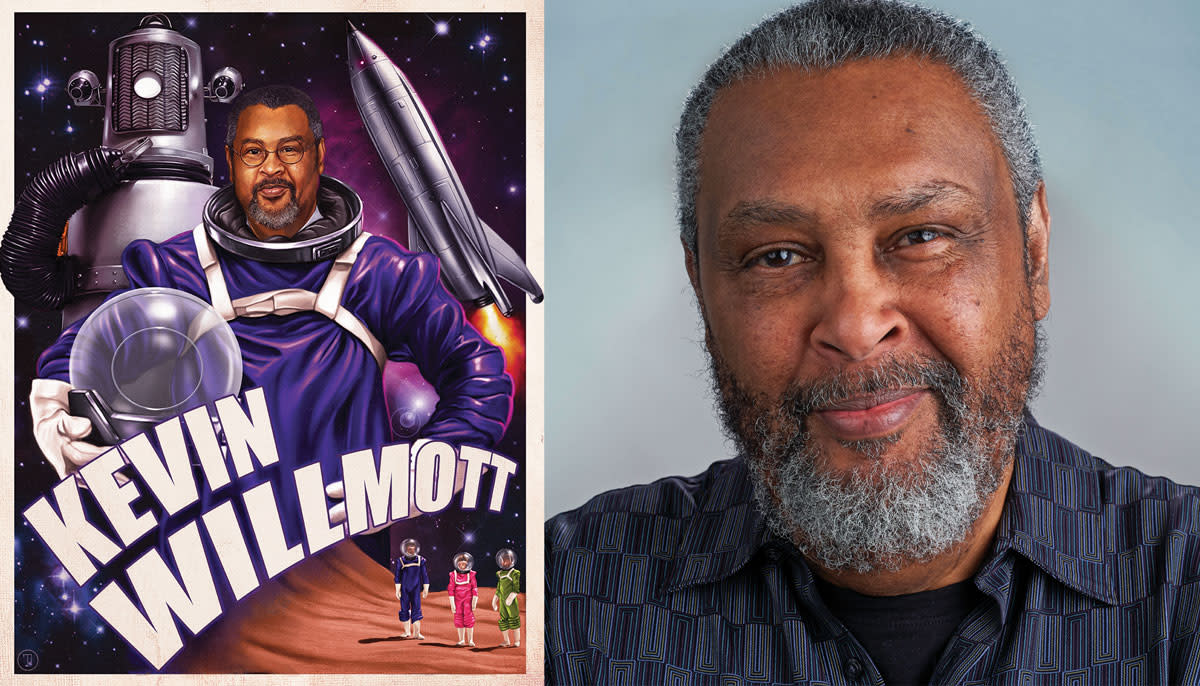

Photography by Carter Gaskins

Photography by Carter Gaskins

Oscar-winning filmmaker Kevin Willmott talks about his life in Kansas, his approach to cinema and his commitment to fighting racism

In February 2019, Kevin Willmott won an Academy Award for co-writing the film BlacKkKlansman. This Oscar presentation followed a series of awards for the film, including the BAFTA (the British Academy award), and the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival. It also brought increased national recognition to a Kansas filmmaker and educator who was already well known for films such as the 2004 CSA: The Confederate States of America and the 2014 documentary of basketball legend Wilt Chamberlain’s college career, Jayhawkers.

From his 1999 film Ninth Street to his most recent release, the 2020 film The 24th, the 61-year-old Junction City native has created fictional and documentary works focusing largely on American history, Black culture and race relations. His artistic creations offer insightful and unsparing critiques of the nation while also dipping into moments of delightful, absurd physical comedy.

For years a professor of film at the University of Kansas, Willmott is recognized as a collaborative creator—someone who builds and supports a community of filmmakers whether that means teaming up with Hollywood legends such as director Spike Lee or promoting his students and younger regional talent.

For this interview, Topeka-based musician and performer Martinez Hillard corresponded with Willmott to talk about Willmott’s work, his life in Kansas and his assessment of where we are as a society in facing the issues his films bring to light.

Martinez Hillard (MH): Can you talk about your earliest remembrance of the social and political atmosphere growing up in Junction City, Kansas?

Kevin Willmott (KW): Junction City was a great place to grow up in the 1960s and 1970s. The Buffalo Soldiers, African American soldiers who served on the Western frontier after the Civil War, lived in my neighborhood. The block I grew up on was the poster child for diversity. Almost everyone was racially mixed and biracial: Black and Korean, Black and Filipino, Black and German, White and Japanese, Black and Italian, Black and Vietnamese. It was great, but the problem was the city didn’t celebrate the diversity. Unfortunately, they were ashamed of it. It gave Junction City a bad reputation because racism was the order of the day. Today Junction City is still very diverse and they should celebrate it! It is their strongest asset!

MH: Can you tell me what your experience was with integrated and segregated education and what you observed as a student through this period of integration?

KW: I went to an integrated school. But more importantly my father went to an integrated school at the turn of the century in Junction City. Kansas [secondary schools were] officially segregated in large cities. That is why Topeka, Wichita, Lawrence, and Kansas City were all segregated. Junction City was too small for segregation, and I recently learned my family left Mississippi to come to Junction City specifically because of the fairness it provided.

Kansas has always had a double nature. It is best described by my friend [Wichita author and educator] Mark McCormick as the “Noble Narrative.” John Brown, the Civil War and Free State, William Allen White—all are positives about the racial history of the state, but there have also always been forces here working against them too. Lawrence, where I currently live, was founded by abolitionists, but then became segregated after the Civil War. Lynching took place here along with the many positives. Kansas has always had a few strong-willed people willing to do the right thing even when they were outnumbered. That is how we should look at it. For me, that ain’t so bad!

MH: I’m curious about your time pursuing degrees at Marymount College in Salina, Kansas, and then at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. I imagine there was a fair amount of contrast between those environments. Can you share what was pivotal about having access to higher education and how it shaped your filmmaking? Also, what barriers did you encounter?

KW: Going to Marymount was like going to another planet for me. We didn’t have a car growing up, and my family never traveled. For me, going 44 miles to Salina was like going to the other side of the moon. My mentor at Marymount was Dr. Dennis Denning, who ran an outstanding theater program, probably one of the best in the country. I learned drama from him. He gave me the opportunity to do my first play with a budget and production design. I wrote the play Ninth Street in his playwriting class. The Little Theater in Junction City refused to do my play because the subject matter [of returning Vietnam War vets facing racial prejudice] was too close to home. But the play won me acceptance into the program at NYU and it would become my first film.

MH: What inspired you to become a civil rights activist during your student years? Why was it important for you to advocate in Junction City, and how did you fold those experiences back into your screenwriting and filmmaking?

KW: I was expelled from high school during [the local] race riots in 1975. The school said get out and don’t come back. The principal at the high school was one of the most racist people I have ever met and I’ve met a lot of racists in my day. [laughs] I worked at the Catholic cemetery on the CETA [Comprehensive Employment and Training] Program, and Joe McCormick was my boss. He helped me to get into St. [Francis] Xavier’s High School where I was educated by the Sisters of St. Joseph. They also educated me at Marymount. They were the best educators in the world. I also met my other primary mentor, Father Frank Coady, who insisted I go to Marymount and supported my goal of being a filmmaker. Being thrown out of high school ended up being the best thing that happened in my entire life. I wouldn’t have an Academy Award if I wasn’t thrown out of school.

For me, I was always able to find acceptance and support as a kid but it was very difficult seeing all the racism around you. It is hard seeing others suffer. They would say “You’re okay, Kevin, but he isn’t.” There were several racist teachers at the public high school. Their job was to control the Blacks. Seeing friends’ lives destroyed by institutional racism was very difficult. I could have looked away and kept my mouth shut, but I didn’t. That’s why I still speak out today. History has taught us to always speak out against discrimination, violence, and injustice. You have to be willing to pay personally for your convictions and beliefs. Getting that lesson at an early age was probably the lesson of my life.

MH: I revisited your film Jayhawkers recently. Mr. Chamberlain’s story—as a Black man, a student-athlete, and a public figure—continues to resonate in our society today. Can you discuss why, in the presence of change and with so many people pushing for it, there remains so much resistance?

KW: Many people don’t believe in America. They would never admit it, but they believe in something closer to white supremacy. They don’t understand how that has woven itself into every aspect of our nation. With every step forward, we see those forces still at work trying to hold onto the past. The best example is how they don’t want to remove Confederate symbols from our society. Elected leaders who question a fair and free election and go so far as to call the system “rigged” should wake up Black in 1917 or 1929 or 1955 or 1968. They should wake up as George Floyd with a knee on their neck. We are seeing how they don’t really believe in democracy when they are now asked to share it with a multiracial nation. They don’t want to live in a nation where the police serve everyone fairly and equally. This fight is only just beginning. Kansas was always on the right side of that fight; I hope we find our place again. Unfortunately, we have lost our way.

MH: You’ve portrayed characters in your films as well. What is special to you about being on that side of the camera, or on stage, delivering those performances? Also, do you think it’s important to screenwriting and filmmaking to perform as well?

KW: I will often act in my films if there is a part I believe fits me, or if the budget demands it. In my film Destination Planet Negro!, I played one of the leads because it was a micro-budget, and I knew I would show up! [laughs] Acting helps your writing; it gives you an ear for dialogue, as well as pace and instinct. Writers should take acting classes or perform in plays to get a better feel for how drama works even if they don’t want to act.

MH: You maintain a friendship and acclaimed working relationship with filmmaker Spike Lee. In addition to Mr. Lee, you’ve worked with lots of talented people. I’d like to know about your experience in collaborating with others and the trust that develops in the filmmaking process. What has to happen in order for a collaboration to feel successful to you?

KW: You have to feel like your collaboration is equal and your voice is being heard and respected. The collaboration has to be a fair give and take. You have to be willing to learn as well as teach. More than anything, the team must put the work first beyond egos and agendas.

MH: Congratulations on being awarded an Oscar for your contribution to BlacKkKlansman! Can you talk about how it feels to have your work recognized by the film industry?

KW: Winning an Academy Award was a dream come true. Watching those shows as a kid with my mother was always inspiring. Only in my fantasies did I think I would be on stage being handed an Oscar. But to be honest, I rarely thought about it. I only thought about the work. I learned from activism that you have to define success on your own terms. I did that with my film career. It kept me going when I was inside and outside of the film industry. I hope to never forget that principle.

MH: Lately there are many questions being asked of awarding bodies and their selection processes across numerous industries. Can you share your thoughts on what responsibility these various bodies have to the industries and creators they celebrate?

KW: Awards equity is really about industry equity. Awards reflect the equity of the business. If our stories aren’t being told, then you can’t compete for awards. If more stories are being told that give people of color jobs, then the awards will reflect that. More people of color need to be in positions to greenlight movies about underrepresented Americans.

MH: You’ve been an educator at the University of Kansas for 20 years. What are some of the conversations you have with your students about storytelling? Has the timbre of those conversations changed with time or are there still rudiments in place that budding filmmakers should always bear in mind?

KW: The big change was film turning into digital. However, the technology may change but storytelling doesn’t. That is still the real challenge. Can you tell a good story? In the end it will always be the same journey and challenge to being a filmmaker. That is the role of education.

MH: What is important to you about having been in Kansas—as a father, educator, and filmmaker—throughout all these years?

KW: Living my life here made me love the state, but it is hard to be a Kansan these days. It is not the state I grew up in. My film CSA: The Confederate States of America is about the South winning the Civil War. That film made me understand how the South did win the Civil War. The best example is the Brown v. Board of Education decision. How did Kansas, the Free State, turn segregated? Well, it listened to the South and adopted their way of life. This is how the South won.

Unfortunately, today the Confederacy is winning even more in our state. We [as voters] rejected the first Black president (even though his grandparents were Kansans) and the first Black woman vice president. We reject health care, gay marriage, and anything that makes the nation and our state a more equitable and tolerant place. … I want people to know our story. It is far from perfect, but there are many things that made it great, and Kansas should celebrate those things. I am proud of Kansas. I remained in Kansas as a choice. Dwight Eisenhower, Langston Hughes, William Allen White, Gordon Parks, William Inge, Amelia Earhart—they are real heroes and Kansans. I feel fortunate that I grew up here and love being part of the legacy that shapes who we are.

Ways to Stay Connected

More Art Stories You'll Enjoy

View ALlFrom the Archives: Remembering John Steuart Curry

Jan 15, 2024Editor's Note: This article was originally published in the winter of 1992 by Don Lambert… Read More

A Paper Moon Pilgrimage

May 19, 2023Photography by Jessi Jacobs Celebrate 50 years of this classic Hollywood film by following the… Read More

Test Your Lumberjack skills with Axe-Throwing

Mar 30, 2023Photography by David Mayes It’s a family outing, date-night fun, stress-reliever and more… Read More

‘Part of the Legacy that Shapes Who We are’

Mar 24, 2023Photography by Carter Gaskins Oscar-winning filmmaker Kevin Willmott talks about his life in Kansas… Read More

Mid-Century Woodworking

Mar 23, 2023Zack Schaffer exudes midwestern modesty. He ranches by day, running several hundred head of cattle… Read More